A World of Words

After meeting Pattabhi Jois in New York over 20 years ago, I left my engineering studies and traveled to Mysore, India to deepen my practice of Ashtanga yoga. Immersed in traditional chanting, I also discovered my passion for Sanskrit.

A few years and a few trips to Mysore later, I returned to school at Columbia University to finish my degree, which turned into an M.A. in South Asian Studies. In the fall of 2006, my first semester, I wrote:

"Although I have written all of my life, it is rare that I let others into that world. I think I always had the notion of public vs. private worlds and words - which thoughts could be shared and which must remain tucked away and unexposed. But writing can serve as a connection, a bridge between the two planes of my existence - internal and external..."

The writing you will find here has evolved since then through different channels - academically, for various publications and just for fun. It is mostly about yoga philosophy and Sanskrit translation and how these can connect us to the essence of yoga in our practice, as well as helping us to be more embodied in our lives.

The ultimate aim of yoga according to the Yogasūtra is kaivalya, the isolation of puruṣa, the male principle, or soul/spirit, from prakṛti, the female principle, or nature. And yet Bhoja, in his commentary on this text, begins by saying that this occurs through the union of Śiva and Pārvatī or Śakti in his form of ardha-nārīśvara, which literally means “the lord who is half woman.”

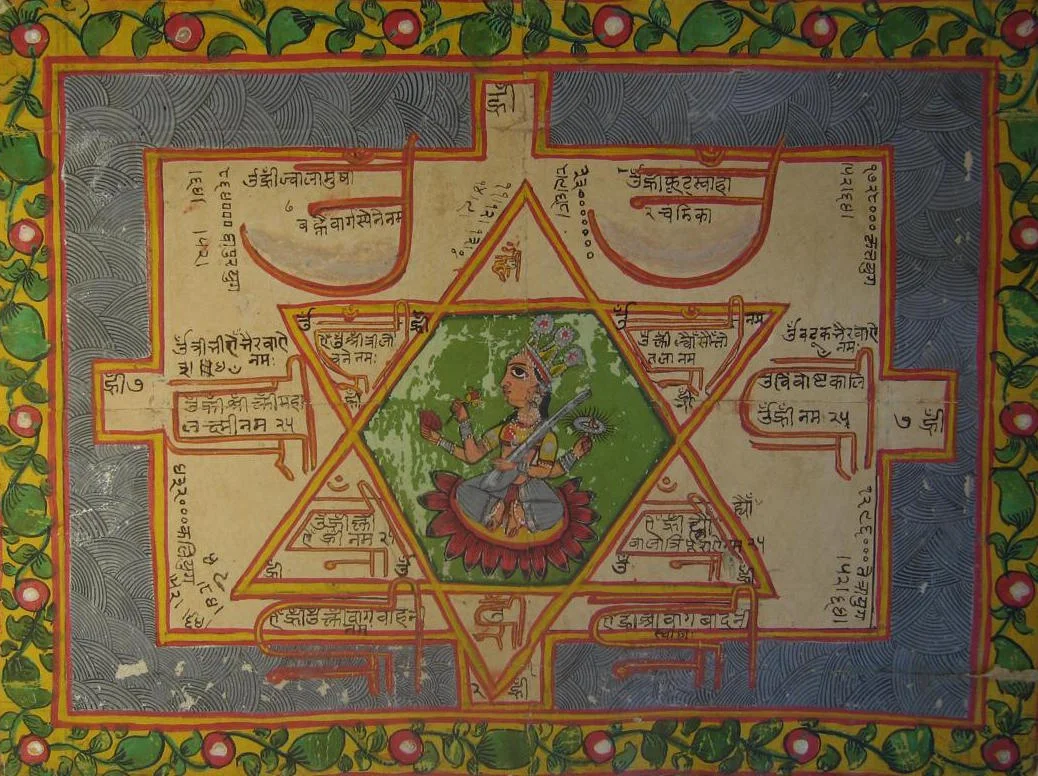

The Sanskrit word “tantra” literally means an instrument for stretching. Traditionally this refers to threads on a loom, but it has come to indicate a system which weaves together various techniques and practices to seek liberation and mystical powers…

These are eight (plus one) verses to the river goddess Yamunā. I was recently asked to translate them by one of my students, whose 80-something-year old aunt recites this every day, but wanted a translation. I think they are so beautiful, I thought I would share them.

One of my favorite Indian stories occurs in Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad 3.9.1, where Vidagdha Śākalya, “the clever grammarian,” repeatedly asks Yājñavalkya how many gods there are. As he keeps asking his question, the answer goes from “three and three hundred and three and three thousand” to thirty-three to six to two to one-and-a-half to one.

The Aparokṣānubhūti provides a concise and accessible entry into Advaita (non-dual) Vedānta philosophy. Its 144 verses teach a method of vicāra or enquiry, which incorporates a fifteen-part system of yoga leading to samādhi, and ultimately to the realization of the oneness of ātman (the individual self) and brahman (the universal Self).

I find myself troubled lately by how frequently verses are quoted on-line without proper citation. Often I read - “The Bhagavad Gītā says,” or “[quote] the Yoga Sūtras.” But the truth is, if it's in English, none of these ancient texts “said” it. It is someone else's translation and interpretation. That being the case, it is important to acknowledge that person, both for their credit and also for the reader to understand the subjectivity involved in what they are reading.

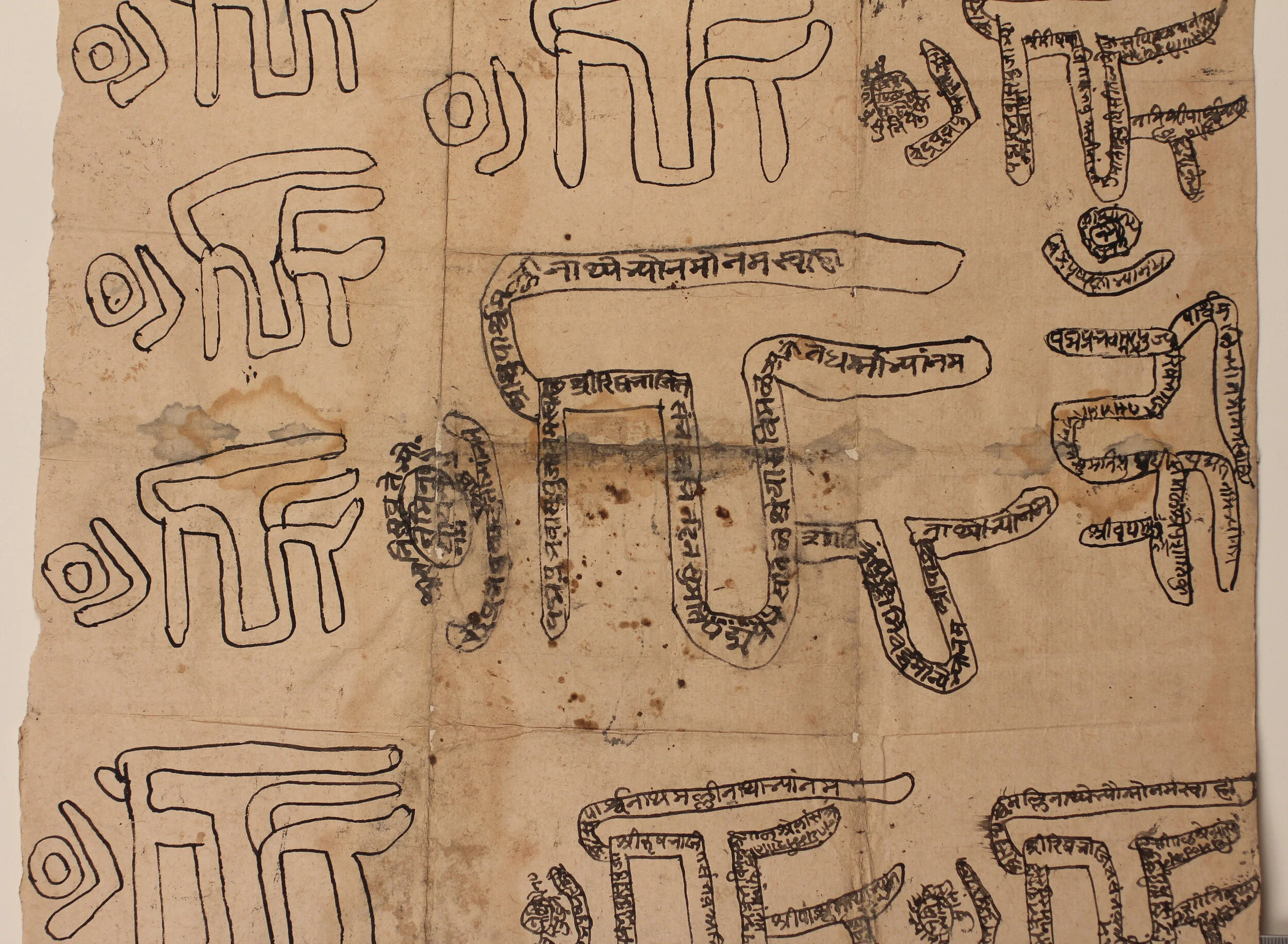

Over the past two years, I've worked with artist Alexander Gorlizki to help translate the Sanskrit, Hindi and Rajasthani text on various yantras (mystical diagrams) and other drawings he collects for his exhibition at the Outsider Art Fair in NYC...

I guess for me the physical asana has always been a tool to go inward. I encourage students if they are stuck at a posture not to look outwards (i.e. towards Facebook or youtube videos) for an answer, but to be present with that discomfort and see what it brings up. Even the frustration, anger and sadness – or whatever emotions may arise - are important. So often these days, people try to avoid sitting with that by putting too much emphasis on mastery of the physical. But our struggles in practice are meant to help us develop concentration and internal focus.

Inevitably if one practices yoga for long enough, one starts to suspect that it has more to do with the mind than the body. As originally described in Sāṃkhya philosophy, we are all born with a particular combination of the three guṇas, “qualities” or “threads,” which determine our individual personality. These three psycho-physical components are rajas (activity or energy), tamas (inertia or stability), and sattva (equilibrium, balance or luminescence).

Part of what I wanted to show in this book is how many choices are involved in translation and to let people in on the process. We do all read these texts through our own individual lens, which is a combination of our cultural, linguistic, spiritual, and psychological backgrounds. We can use the process of translation to become more conscious of our own perspective and our ways of seeing the world...

I think every teacher I’ve had has taught differently and all of the different styles have become a part of me, and how I read and understand and chant and teach Sanskrit. Perhaps more than anything, I still hear Guruji’s voice rapidly reciting verses or sutras and the burning desire it sparked in me to understand and keep up with him and to be a part of that magical world.

Guruji always used to say that ashtanga yoga is Patañjali yoga. Although there may not be explicit correlations between the sūtras and the ashtanga vinyasa method, the sequences of postures can be considered to embody these teachings in various ways. One way to explore this relationship is to consider the three ingredients of kriyā yoga discussed above, in conjunction with the fundamental components of ashtanga yoga.

I first met Guruji in the skylight ballroom of the Puck building in downtown New York City. It was pure magic – the sun rising, Guruji counting in Sanskrit, “the language of the Gods,” hundreds of people breathing in unison. I was twenty years old and had been practicing ashtanga yoga for a few years, but those mornings I felt something deep within me begin to awaken. I was filled with a sense of peace and inner happiness I had never experienced before.

I would now like to entertain the idea that this basis in polarity, itself, could contribute to the difficulty in understanding the yamas and niyamas and making sense of them within our lives. We could instead allow for a broader spectrum of possibility, rather than limiting our language, our thoughts, and thus our vision of reality to polar opposites, such as violence and non-violence, truth and untruth, celibacy or unconscious sexuality, purity or pollution. What if we made space for a reality to emerge that acknowledges the shades of grey, the rich complexities that are an inescapable part of being human?

If we deny or try to suppress a piece of who we are then we are not practicing yoga, we are not fulfilling our dharma (duty). Many Westerners misunderstand yoga - we think it is about withdrawal from the world, about abstinence, when in fact it should be a means to living more fully in the world, in all of our various individual capacities. The practice of yama and niyama is what situates a yoga practitioner in the world...

We all look, but do we see? How often do we bring concentrated awareness into our everyday viewing? Our eyes are the lens through which we learn about the world and ourselves in connection with the world, the very same tool through which we can discover the connection between the external and internal self.

The study of Sanskrit is a practice - it is a meditation, a contemplation, a way of focusing the mind. The level of concentration required creates a form of dṛṣṭi, of one-pointed attention. One becomes immersed in the sound, the meaning, the characters themselves. These days, when we can find any information we want in a moment in a Google search, the value of slow contemplation is all the more important.