As published in Pushpam Magazine

On Mantras and Oṃ

by Zoë Slatoff

One of my favorite Indian stories occurs in Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad 3.9.1, where Vidagdha Śākalya, “the clever grammarian,” repeatedly asks Yājñavalkya how many gods there are. As he keeps asking his question, the answer goes from “three and three hundred and three and three thousand” to thirty-three to six to three to two to one-and-a-half to one.[1] Ultimately the many gods just represent different aspects of understanding the singular, all-encompassing reality. One could ask a similar question about how many mantras there are, beginning with an infinitely large number and eventually reducing to three and then to one. The three would be the vyāhṛtis, or worlds: bhūr (earth), bhuvaḥ (atmosphere), svaḥ (heaven). The one would be Oṃ. Said to contain everything, it is known as the primordial sound. In the Upaniṣads, Oṃ is considered an auditory form of Brahman, the Universal Self, or a means to its realization.

Literally an “instrument of thought,” a mantra is used as a tool to focus the mind. It is one of the main techniques for achieving this in the Yogasūtra. It first occurs in sūtras 1.27-29, which explain that the word signifying īśvara (God) is praṇavaḥ or Oṃ and that through the repetition (japa) and contemplation of its meaning, there is the realization of the inner consciousness, or seeing one’s own Self, and the absence of all obstacles.[2] In this context, it is just one option given for developing one-pointed concentration and ultimately attaining samādhi (absorption).

The word japa refers to muttering prayers and it is thought that unlike the way in which mantras are often chanted in modern yoga classes, the more quietly and internally a mantra is recited, the more powerful it is. According to the Yogayājñavalkya (2.15cd-16): “a mantra uttered in a low voice is said to be a thousand times more powerful than loud mantra repetition […] Mental recitation is said to be a thousand times more powerful than a mantra uttered in a low voice. And, likewise, meditation, is said to be a thousand times better than mental recitation.”[3] This represents the crucial difference between japa and svādhyāya (recitation), which are often used almost interchangeably except that the latter is more commonly performed aloud.

The second chapter of the Yogasūtra, the sādhana pāda, or chapter on practice, provides more accessible means for learning how to make the mind less agitated and more ready for concentration and one-pointed attention. This begins through the path of kriyā yoga, the yoga of action, which consists of tapas (discipline), svādhyāya (study of scripture), and īśvara-praṇidhāna (surrender to the Divine). These elements also appear later in the chapter as the last three components of niyama (observances), the second limb of aṣṭāṅga yoga. Although svādhyāya is often literally translated as “self-study,” this can be misleading, causing people to think that it means a psychological study of oneself, perhaps even facilitated by therapy, but this would be mistaking the Self for the ahaṃkāra or ego. Sva does indeed mean self, but adhyāya comes from the verb adhy-i, meaning to go over or memorize, which is an essential part of oral tradition. Traditionally it refers to chanting Oṃ or studying sacred texts. Svādhyāya can thus be better understood as personal or individual recitation. When this involves study and repetition of sacred texts, these texts have the goal of liberation and realization of the Self, which is the true meaning of “Self-study.”

Our current ways of understanding svādhyāya come mostly from Krishnamacharya’s 20th century students. In Pattabhi Jois’s traditional explanation, “Swadhyaya is the recital of Vedic verses and prayers in accordance with strict rules of recitation. Vedic hymns must be recited without damaging the artha [meaning] and Devata [deity] of a mantra through the use of a wrong swara [pitch] or the improper articulation of a akshara [letter], pada [word], or varna [sentence].”[4] A footnote to this definition explains that, “in mantras, word, form, and meaning are one, and inextricably connected.”[5] In other words, correct mantra recitation both requires and develops concentration. T.K.V. Desikachar defines it as “self-inquiry; any study that helps you understand yourself; the study of sacred texts.”[6] And according to B.K.S. Iyengar, “Svādhyāya means the study of the Vedas, spiritual scriptures that define the real and the unreal, or the study of one’s own self (from the body to the self).”[7] These latter ideas of moving from external to internal and learning to understand ourselves fit a bit more into our current understanding of the concept in relation to āsana practice, but they drift away from the traditional meaning. Unless the study that is undertaken leads towards the realization that we are not the body or the mind, Desikachar and Iyengar are really redefining the concept, even though it is still set within the framework of the Yogasūtra.

Repetitive practice is what is known as abhyāsa, which along with vairāgya (detachment) are the tools for stilling the fluctuations of the mind, which is the definition of yoga for Patañjali.[8] Through repetitive practice we are able to minimize the negative saṃskāras (mental impressions) and replace them with positive ones. In my experience, both practicing and teaching, this is what can happen through the repetition involved in aṣṭāṅga yoga. Slowly, over time, our mental patterns can change, even if only in small ways. This is exactly what is meant to happen through the recitation of Oṃ. Eventually one’s saṃskāras become less agitated and distracted and more sattvic (equanimous), concentrated and conducive to meditation. Therefore through action, one learns to go beyond action. Through the body, one learns to go beyond the body.

In sūtra 2.44, it is said that from svādhyāya there is union with the desired manifestation of God.[9] According to Bhoja’s commentary, “the idea is that God is experienced directly.” This leads us back to the beginning - if all gods are really just the one true reality, then this brings us to the ultimate realization of Brahman. Or in a more worldly sense, as Pattabhi Jois explains, “Gods related to the mantras give siddhis [powers] to those who chant them and ponder their meanings.”[10] Mantra is mentioned again in the first sūtra of the fourth chapter of the Yogasūtra. Here it is specifically listed as one of the means of attaining siddhis or supernatural powers. It refers to Vedic mantras, which were used to try to influence cosmic forces to produce desired results.

Among all of these mantras, the gāyatrī is the root, just as Oṃ is the root of all sound and by extension, the whole world. In a verse contained in both the Dharma Sūtras of Baudhāyana (4.1.22) and Vasiṣṭha (25.4), svādhyāya is instructed to be done with regulated breath: “Seated with purificatory grass in hand, he should control his breath and recite the purificatory texts, the vyāhṛtis, the syllable Oṃ, and the daily portion of the Veda.”[11] In another verse contained in both texts, “prāṇāyāma is defined as reciting of Oṃ, the vyāhṛtis and the Gāyatrī three times ‘while controlling the breath’ (āyataprāṇa).”[12]

Pattabhi Jois also emphasized that “the Gayatri mantra forms the basis for the study of all Vedic verses, or mantras.”[13] The gāyatrī is a chant to the three worlds and everything encompassed within them. It is traditionally taught to young boys at the upanayana or thread ceremony, which is the rite of passage into adulthood and the beginning of Vedic studies, but perhaps we can all learn it to plant our minds with seeds or positive saṃskāras.

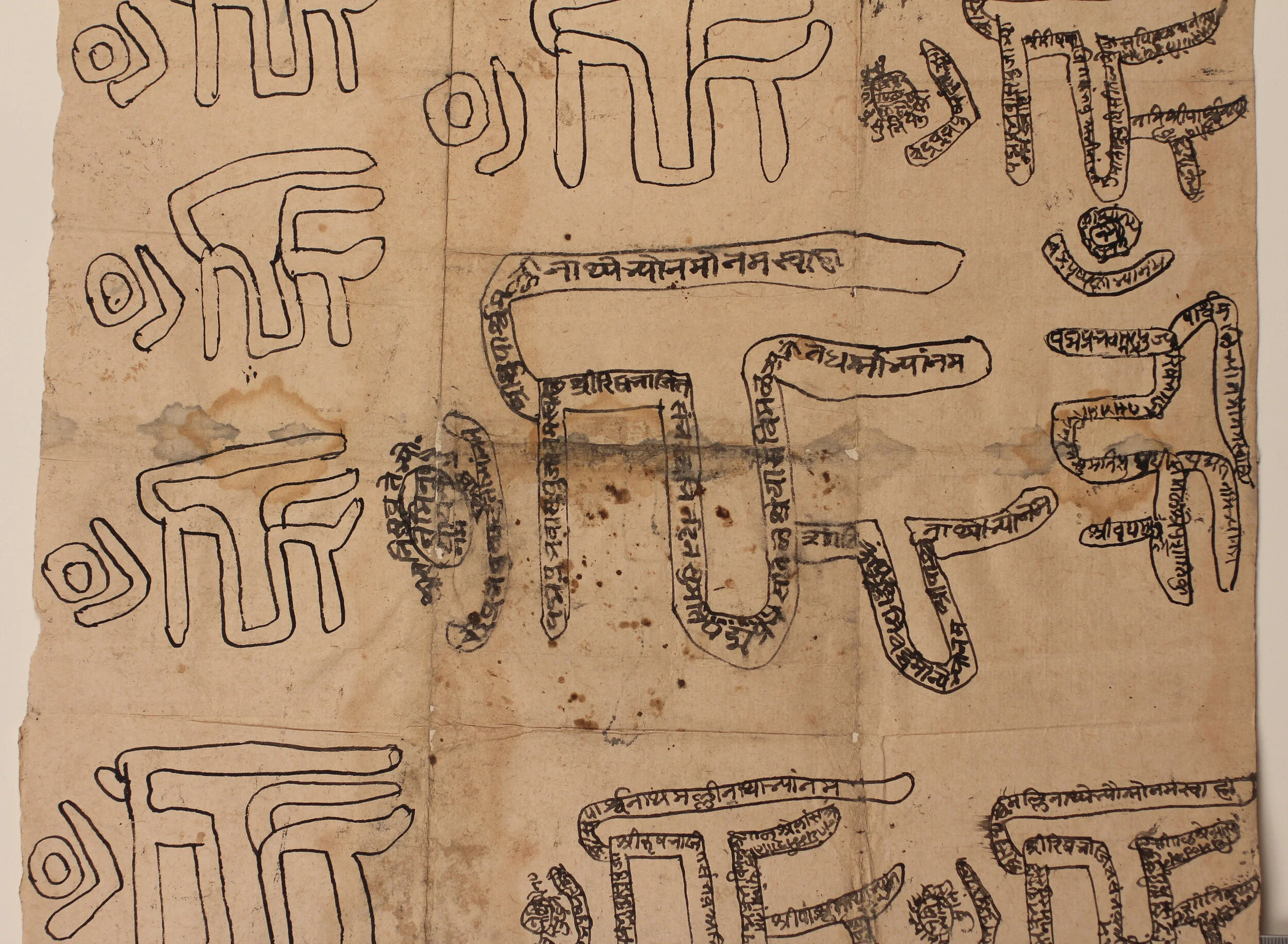

ॐ भूर्भुवः स्वः । तत्सवितुर्वरेण्यम् ।

भर्गो देवस्य धीमहि धियो यो नः प्रचोदयात् ॥

Oṃ bhūr bhuvaḥ svaḥ | tat savitur vareṇyam |

bhargo devasya dhīmahi dhiyo yo naḥ pracodayāt ||

Earth, atmosphere, heaven.

The excellent divine power of the sun.

May we contemplate the radiance of that god.

May this inspire our understanding.

Notes

[1] Olivelle, Patrick, trans. and ed. (1998). “The Early Upaniṣads: Annotated Text and Translation.” New York: Oxford University Press, p. 93.

[2] Yogasūtra 1.27 -29: tasya vācakaḥ praṇavaḥ | taj-japas tad-artha-bhāvanam | tataḥ pratyak-cetanādhigamo ‘py antarāyābhāvaś ca |

[3] All translations are my own unless cited otherwise.

[4] Jois, Sri K. Pattabhi. (1999). “Yoga Mala.” New York: Patanjali Yoga Shala, p. 27.

[5] Jois, p. 27.

[6] Desikachar, T.K.V. (1999/1995). “The Heart of Yoga.” Vermont: Inner Traditions International, p. 242.

[7] Iyengar, B.K.S. (2002/1993). “Light on the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali.” London: Thorsons, p. xv.

[8] Yogasūtra 1.2: yogaś citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ |

[9] Yogasūtra 2.44: svādhyāyād iṣṭa-devatā-samprayogaḥ |

[10] Jois, p. 27.

[11] Carpenter, David. (2003). “Practice makes perfect: the role of practice (abyāsa) in Pātañjala yoga.” In Whicher, Ian and Carpenter, David, eds., “Yoga: The Indian Tradition.” London: Routledge-Curzon, p. 31.

[12] Carpenter, p. 31.

[13] Jois, p. 27.

Bibliography

Carpenter, David. (2003). “Practice makes perfect: the role of practice (abhyāsa) in Pātañjala yoga.” In Whicher, Ian and Carpenter,

David, eds., “Yoga: The Indian Tradition.” London: Routledge-Curzon.

Desikachar, T.K.V. (1999/1995). “The Heart of Yoga.” Vermont: Inner Traditions International.

Iyengar, B.K.S. (2002/1993). “Light on the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali.” London: Thorsons.

Jois, Sri K. Pattabhi. (1999). “Yoga Mala.” New York: Patanjali Yoga Shala.

Olivelle, Patrick, trans. and ed. (1998). “The Early Upaniṣads: Annotated Text and Translation.” New York: Oxford University Press.