Kriyā Yoga

by Zoë Slatoff

तपस्स्वाध्यायेश्वरप्रणिधानानि क्रियायोगः ।

tapas-svādhyāyeśvara-praṇidhānāni kriyā-yogaḥ

The yoga of action consists of discipline, self-study and surrender to the Divine.[1]

Yogasūtra 2.1

The first sūtra of the second chapter of the Yogasūtra sets forth the path of kriyā yoga, the yoga of action. The three essential ingredients are tapas, discipline, svādhyāya, self-study, and īśvara-praṇidhāna, surrender to the Divine. Tapas means discipline or austerity. Derived from the verbal root tap, to heat or burn, it can be thought of as a burning devotion, an intense self-discipline, such as āsana practice. Like any fire, it must be stoked steadily and consistently. Practice too little or without steady focus and the fire may go out; practice too much or too intensely and you may burn out. In order to help cultivate the discernment necessary to support this discipline, the second element is svādhyāya, self-study, a form of deep introspection. Traditionally this can take the form of japa, or the repetition of mantras, such as oṃ. However, it can also be thought of as more of a psychological study of oneself, dealing with the emotions that often surface during yoga practice. Only by honest self-inquiry is it possible to continue the discipline over a long period of time. To help us be present with whatever arises in this process, the third element is īśvara-praṇidhāna, a surrender to the Divine or offering up of one's efforts to the Supreme Soul, in whatever way that personally makes sense. It is a relinquishing of the fruits of one's actions, as Krishna advises in the Bhagavadgītā, a relaxing of goal-oriented effort. It is the faith that carries us forward every day, and that helps us keep practicing even when it is difficult. All three of these components - discipline, self-study and surrender - are important and must be practiced in conjunction.

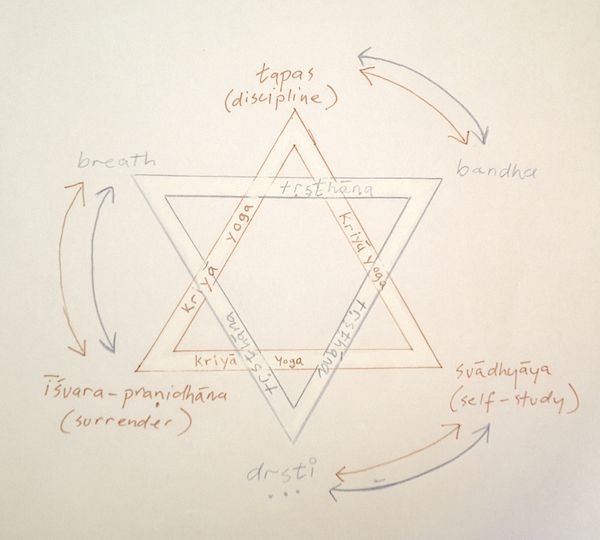

Guruji always used to say that Ashtanga yoga is Patañjali yoga. Although there may not be explicit correlations between the sūtras and the ashtanga vinyasa method, the sequences of postures can be considered to embody these teachings in various ways. One way to explore this relationship is to consider the three ingredients of kriyā yoga discussed above, in conjunction with the fundamental components of Ashtanga yoga. These components are collectively called tṛsthāna, “the three places” on which we fix our attention in ashtanga yoga - bandha (or posture), dṛṣṭi, and breath. They work together and are mutually interdependent, similarly to tapas, svādhyāya, and īśvara-praṇidhāna.

In this respect, bandha (or posture) can be considered as analogous to tapas - it is the discipline, the engaged action, the fire element that ignites and sustains the practice. It is the invisible essence that roots us in the physical practice and signifies continuous commitment. The dṛṣṭi, the nine gazing points that are used to focus the eyes and attention, can be considered the svādhyāya, the means to introspection. The eyes draw us from the external to the internal and through constant focus, a state of pratyāhāra, or sensory withdrawal is continuously created. The steady, rhythmic breath with sound that is cultivated throughout practice can be considered as the īśvara-praṇidhāna. The breath is the means to surrender and our link to the Divine.

Through this analogy, Ashtanga yoga can (perhaps unsurprisingly) be considered the yoga of action. These three components should ideally be in equal proportion: equal effort, surrender and focus. The intense discipline and strength of tapas or bandha is equally as important as the lightness and grace of the breath or īśvara-praṇidhāna. And the dṛṣṭi or svādhyāya is the link between the two. It is easy to be seduced by the effort or bandha or posture, the power of the external form is compelling. When you are working on a challenging new pose, it is tempting to escape the more internal aspects of practice by watching videos or taking workshops. But what gets lost in the process is the focus and surrender it takes to figure it out for oneself, the dṛṣṭi and the breath disappear. In my experience, it is the pose that you can't do that is essential and the challenge is to sit still with that inability, even when it pushes you to an edge. To me, the physical and emotional issues that arise from working on a difficult pose are the crux of the practice and what really teach you svādhyāya and īśvara-praṇidhāna.

The second sūtra of the second chapter explains that the purpose of kriyā yoga is actually for bringing about samādhi and weakening the afflictions. This is the underlying intention of uniting these three elements together.

समाधिभावनार्थः क्लेशतनूकरणार्थश्च ।

samādhi-bhāvanārthaḥ kleśa-tanū-karaṇārthaś ca

The purpose of kriyā yoga is for bringing about samādhi and for weakening the afflictions.

Yogasūtra 2.2

अविद्यास्मितारागद्वेषाभिनिवेशाः क्लेशाः ।

avidyāsmitā-rāga-dveṣābhiniveśāḥ kleśāḥ

The afflictions are ignorance, egoism, attraction, aversion and fear of death.

Yogasūtra 2.3

How does the practice of Ashtanga yoga help to weaken these afflictions? Slowly, day-by-day, we are working through these mental patterns. As we learn new poses or work steadily (or sometimes not so steadily) on old ones, we come face to face with our own ignorance, or literally the absence of knowledge - our inability to perceive things as they truly are. This ignorance is thought to be the field from which all the other afflictions arise.[2] It is the incapacity to truly see what exists in front of us that causes us so much pain and suffering. It is this ignorance that leads to identifying with our egos, to attractions and aversions and to the fear of death. These attachments and fears are often what keep us stuck in patterns that prevent us from fully living. According to Patañjali, this is the mistaking of the transient for the eternal, the impure for the pure, suffering for happiness, and the non-self for the self.[3] In other words, we delude ourselves into believing something is real that isn't, thinking we know when we don't, like the classic example of mistaking a rope in the road for a snake. In modern yoga practice, this often happens by mistaking physical perfection in an āsana for the goal of yoga practice or as indicative of some kind of inner peace. In modern yoga scholarship, this can happen by mistaking theoretical knowledge for practical experience. Of course I am liable to fall into both of these traps at various moments, but perhaps this can be considered svādhyāya itself!

In the Yogasūtra there are only two sūtras providing instruction on āsana.

स्थिरसुखमासनम् ।

sthira-sukham āsanam

The posture should be steady and comfortable.

Yogasūtra 2.46

प्रयत्नशैतिल्यानन्तसमापत्तिभ्याम् ।

prayatna-śaitilyānanta-samāpattibhyām

This is attained through relaxation of effort and meditation on the infinite.

Yogasūtra 2.47

The reason only one pose is taught at a time in Ashtanga yoga is so that you can find a relative degree of sukha or ease before moving on. The yoga postures are meant to be a vehicle for all of the other aspects of practice, including the yamas and niyamas, beginning with ahiṃsā, non-violence. In the Yogasūtra, no postures are referenced at all, but in Vyāsa's commentary (considered the first and primary commentary on the sūtras and possibly even an auto-commentary), all those that are mentioned are seated or supine poses. The reason for this is that the body is meant to be in a relative state of ease in order to find meditation and the higher states of yoga. The “relaxation of effort” referred to in Yogasūtra 2.47 is key. Although it may take time to understand how to do this and there may be pain and soreness along the way, over time, the aim in āsana should be a relative level of ease and comfort in the body, or else the mind will never find peace.

This brings us back to the beginning, to the tṛsthāna, the three-fold means of action, which help to cultivate the concentration necessary for practice. These days, in order to pay attention to these details and to create this state, we really have to make a concerted effort so as not to be distracted by the constant sensory overload and demands for our attention, even for just an hour or two. There are many obstacles and distractions to our concentration...

Here are just a few practical guidelines to help integrate these principles:

- Turn off your phone before practice and do not turn it on again until after you are done.

- Shower before practice and make sure your mat and clothes are clean; do not wear perfume/cologne. Any smell can divert your attention outwards as well as being a distraction to others.

- Come into the practice room quietly; do not talk as you enter.

- Take an empty spot and commit to it. Be aware of your own attractions and aversions and try not to give them too much power. All spots in the room are created equal!

- As soon as you put your mat down, you begin cultivating prāṇa, the life force. If you move your mat during practice you are giving up all of the prāṇa you have cultivated so far in your practice, not to mention disturbing those around you.

- Focus on your dṛṣṭi throughout practice, try not to look around the room at other people's practices - this takes you out of your own state of pratyāhāra, as well as disrupting the practice of whomever you are looking at.

Of course, rules are made to be broken and too much rigidity can cause its own set of problems, but it is important to try to invoke this underlying order within your own practice. It is within this order, that you can cultivate a deep state of concentration and meditation. And it is that state, which is the aim of both of the three-fold practices spoken of above - a living realization of yoga itself.

[1] All translations are my own.

[2] avidyā kṣetram uttareṣāṃ prasupta-tanu-vicchinnodārāṇām || Yogasūtra 2.4 ||

[3] anityāśuci-duḥkhānātmasu nitya-śuci-sukhātmā-khyātir avidyā || Yogasūtra 2.5 ||